|

| Lord of Destruction |

In ENG312 (Writing and Culture): Anime we have watched some of the greatest anime films ever made and discussed anime as an art form and medium for philosophical expression in many ways. We’ve talked about serious issues like war-torn Japan and Grave of the Fireflies, post-war Japan and Akira, as well as romantically inspired stories like Paprika and the otherworldly fantasies of Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki. Being a long-time fan of anime there is one thing that stood out to me that we had largely not covered (and with good reason): Hentai.

Hentai is a genre of animated erotica originating in Japan alongside anime and manga. Hentai is the word by which is it known by Western audiences whereas, in Japan itself, it is known more commonly by the term ero manga/seijin manga or for anime, ero anime/seijin anime. Seijin meaning “adult.” The term “hentai,” in Japan, more often refers to perversion or a pervert.

Hentai is an important part of anime culture because there is hentai produced of literally every anime character ever made. Even hentai of popular child-targeted films such as Spirited Away are accompanied by fan-made erotica featuring child characters in horrific adult situations. I encourage any who doubt these claims to merely perform a Google image search combining the title of your favorite anime with the word “hentai.” You will obtain results whether you like them or not.

If an anime is large enough to have an audience, it is large enough to have hentai existing of its characters. More often than not, fan-made hentai is produced for anime characters of a child appropriate anime series or film. Hentai productions are not fan-made but produced by a studio and feature original characters.

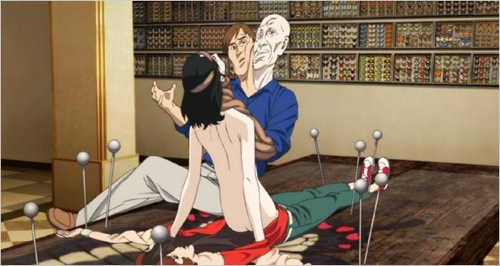

When looking through the pictures featured in Susan Napier’s Anime: From Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle, I saw the picture depicting tentacle rape in Urotsukidoji: Legend of the Overfiend (1987). This was from the scene in the beginning of the OVA in which Akemi is molested and raped by her demon-possessed high school teacher. Finding something of such adult nature, and such perverse nature, in a book assigned for a class peaked my interest immediately in the film. I was also enticed by the fact that it was clearly vintage – sharing a similar design style to that of popular TV anime series Yu Yu Hakusho: Spirit Detective (1990).

|

| DOUBLE DEMONS ALL THE WAY ACROSS THE REALMS?! |

|

| Hiei is a similarly un-sided character in Yu Yu Hakusho |

Amano of Urotsukidoji and Hiei of Yu Yu Hakusho

Interestingly enough, Urotsukidoji and Yu Yu Hakusho have more in common than just their vintage anime art style. Both stories feature the Japanese high school backdrop as their setting and feature high school students (or young looking characters) as the main characters. Even more, they both feature the demon realm and demon invasions of the human world as important parts of their plot structures.

Urotsukidoji differs from Yu Yu Hakusho in that it is a three-part OVA and its plot is immediately apocalyptic in nature. The word “urotsukidoji” translates to “wandering child” in English; this is referring to Amano Jyaku who is the lead role in the story. He is a half-man half-beast who has been banished to the human realm by The Great Elder to search for the Chojin (the super deity) of the legend. The Chojin is said to awaken, reincarnated, every 300 (or, in the anime translation, every 3,000) years to destroy and recreate the world. The story begins with Amano sniffing out, as it were, the boy who has been born with the dormant Chojin waiting to awaken inside of him. Amano’s intentions seem to be unintrusive in nature – he expresses delight at witnessing the Chojin and seeing the new world it creates. His attitude conflicts, later on, with that of The Great Elder who knows the truth about the Chojin. Amano is rivaled by demons that are also in search of the Chojin and wish to eliminate or cooperate with the Chojin.

Urotsukidoji is known as the key predecessor to the tentacle-rape genre of hentai animation. When Toshio Maeda released the Demon Beast Invasion some years later, it became a well established and very popular genre. Another hentai that Maeda produced, which became just as (if not moreso) popular than Urotsukidoji, is La Blue Girl (1992) that lightly parodies the tentacle-rape genre.

|

| You want to do what to my what? |

So, at this point, you’re probably wondering where the perverse nature and tentacles of Urotsukidoji come in. The film brings in its adult themes with the demons and beasts present in the story. These supernatural beings are obsessed with sex and love to engage in monstrous sex and violence towards humans and when the Chojin awakens to collapse the human, beast and demon realms, all hell literally breaks loose.

What has struck me and many other fans of anime as a key quality of the films is the realistic drama between characters and a search for self-actualization or meaning. This is where I feel that Urotsukidoji and the majority of other hentai film series deviate from typical anime. Without a doubt, the factor that drives the plot of Urotsukidoji is a sexual one and the factor that constantly refrains from delineating the linear plot structure set in place is Amano’s constant willingness to sit by and watch on the sidelines. Through Amano, we see what he sees and we hear his commentary but, despite the protests of The Great Elder, he never attempts to challenge the awakening of the Chojin.

|

| H.P. Lovecraft would be proud. |

The Lord of Destruction awakens in Nagumo, following his being hit by a car. In a morgue, his body grabs the hand of a nurse and the Lord possessed Nagumo rapes her, and in his orgasm, bursts her body cavity open. He then destroys the hospital as he transforms into the full-sized Lord of Destruction and towers over the city. The state is short-lived and Nagumo returns to school and normal health. After this catastrophic event, Amano takes Nagumo to the demon realm (accompanied by his half-beast sister), and is then warned by The Great Elder.

Ideally, this would have been the point where Amano or someone would have killed Nagumo to prevent the destruction of the realms. But, even at that, there would still be the dilemma of the fact that it is not necessarily Nagumo’s fault that he was born with the Lord of Destruction inside of him. At any rate, this is the one factor that blatantly marks this narrative progression as being different from a typical movie where there exists a “good” protagonist.

This is where I believe we can identify Urotsukidoji as being an apocalyptic dark fantasy. One in which there is no hope of humanity being saved. This is a world in which all of the worst things imaginable are going to happen and there is nothing anyone can do about it. The implication being that the stage is set and the audience gets to sit back and enjoy the ensuing chaos of rape and violence.

Another marker that differentiates this story from those of popular mainstream productions is the fantasy romance that takes place. Nagumo’s crush, Akemi, falls hopelessly in love with him after her being raped by her teacher. Amano and Nagumo save her from the clutches of her teacher, after delightedly spying on the affair through the cracked door, and Nagumo takes her on a date in the park.

In classic damsel-in-distress fashion, she begs Nagumo to tell her that the rape was all her imagination. He obliges, embraces her, and shortly following they begin to engage in heavy petting in the bushes.

|

| Spyin' on peoples in the parks. Touching myself inappropriately. This is totally normal. |

Akemi is the total embodiment of the aversive male sexual fantasy. Her character is the polar opposite of realistic, if reality had a polar opposite. She will get raped but she will eventually submit and enjoy it, shortly following she will beg for romantic gratification to the least likely candidate, and despite him revealing himself to be only driven by sexual motives she will still fall hopelessly in love with him. Her unquestioning love for Nagumo, of course, ultimately results in the conception of the Chojin – The Super Deity.

Akemi’s character agrees by Susan Napier’s statement about magical girlfriends, “… far from being radical statements of feminine independence, these alternative visions are usually undermined by a fundamentally conservative narrative structure in which the female continues sacrificing herself for the sake of the male.” [Napier p.197]

So, why doesn’t the Lord of Destruction’s seed burst her body cavity open like the nurse in the morgue? Presumably, this is because Nagumo’s dormant soul and infatuation with Akemi represses the violent nature of the demon and assures a safe delivery of the seed. And, in a story as fantastic as this, it doesn’t require much further suspension of disbelief that impregnation is instantaneous.

I’d like to assert or reiterate that this hentai exists as a resounding realization of the male sexual fantasy. Napier confirms a preexisting agenda by which the story arch conforms when she discusses the appeal of romantic anime fantasies across genders. In her concluding statement in her chapter on the magical girlfriend versus the shoujo she claims, “… these narratives are essentially from the male point of view. In a world where women (and life in general) seem increasingly out of control, the notion that certain truths about love and relationships in which the male identity remains stable and the male ego is restored rather than destroyed may have more appeal than ever. It is surely no accident that the ‘magical girlfriends’ depicted in these series are not only magical but also alien – an implicit recognition that such marvelous fulfillments of male dreams now exist only in an alien world far from reality.” [Napier p.212]

|

| Hi-Laser Tentacle Penises. 'Nuff said. |

Immediately following, the Lord of Destruction takes full form (resembling Cthulu in many ways) and proceeds to destroy Osaka, Japan with its hi-laser tentacle penises. The decimating of Osaka seems to pay homage, in a way, to Akira as the resulting blast that destroys the Demon of the Sea creates a wall of light that engulfs the entire city. After the drama between the various surviving characters settles down and Amano resolves that he will simply “survive,” the Legend of the Overfiend repeats itself to conclude the story. The conclusion is essentially that the Chojin will be born, the realms will be destroyed, and new ones will be created. Where most typical anime films contradict the audience’s expectations and creates a happy ending, Urotsukidoji gives us a linear plotline that aims to disappoint.

There is a repetition of the legend at the beginning of each volume of the OVA. At the end of the final volume, it repeats again. This repetition of the legend at the end of the narrative is a very powerful statement. In layman’s terms it says, “I told you that this would happen. You have only yourself to blame for seeing it through.”